We recently spent three weeks traveling around the beautiful country of Vietnam. From the beaches to the mountains and in between, it's a gorgeous place. Even more gorgeous are all the smiling faces of the kind, welcoming Vietnamese people.

As we explored all that Vietnam has to offer, we learned more about the violent wars that the country has endured, particularly in the past century. With every day and every new piece of information, those smiles we saw became even more beautiful, because we understood them in the context of Vietnam's very sad history.

Let's go waaay back to sometime in middle school. (Fun fact: Mike and I went to the same middle school, but not at the same time!) For us, world history was covered in social studies class. At some point, although I can't remember which grade, we first learned about the Vietnam War.

Maybe we were too young to grasp the horrors that happened, or maybe it was just another chapter in the textbook that we've since forgotten, but honestly, Mike and I both agreed that we didn't fully understand the war or the USA's role until we educated ourselves in the country where it all went down.

While in Vietnam, we sought out different experiences to learn more about what happened. We sort of felt it was our duty, being young Americans fortunate enough to travel as we currently are. Even more than that, visiting historical sites and museums is something that we often feel compelled to do in order to walk away feeling like we earned the right to enjoy our time in a foreign place.

So, here's a brief overview of the historical sites and museums dedicated to the American War (as they refer to it in Vietnam) that we visited in Vietnam.

Hoa Lo Prison in Hanoi

The Hỏa Lò Prison was originally built by the French colonists in Vietnam to hold political prisoners, then later used during the Vietnam War by North Vietnam for prisoners of war. It held many American POWs (including John McCain), who gave it the nickname "the Hanoi Hilton."

This was our first taste of the discrepancy between how the U.S. describes certain aspects of the war and how it looks through Vietnam's eyes. The fair treatment of American soldiers was emphasized (and likely exaggerated).

War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City

The majority of the War Remnants Museum is dedicated to exhibits relating to the Vietnam War (there are also a few about the first Indochina War with the French colonialists). This museum was easily the most harrowing for us. In particular, one large exhibit room contained more than 100 photographs showing the damaging and lasting effects of Agent Orange on Vietnamese men, women and innocent children.

We also saw those affected firsthand in the streets and working at centers for disabled persons. The most horrible realization is that the damage to so many innocent lives could have been avoided. For us at home, the war is over. It is rarely talked about and for many, rarely thought about. But for the Vietnamese, reminders are everywhere.

Although it's very sad, it's also very informative. This museum offers a powerful experience that is not to be missed.

One of the U.S. helicopters on display outside the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City

Cu Chi Tunnels (north of Ho Chi Minh City)

The day after we went to the War Remnants Museum, we joined a small tour group to visit the Củ Chi Tunnels north of the city. The Cu Chi tunnels are a network of underground tunnels that were used by North Vietnam fighters during the war (both for combat and living in hiding). They are just one connected system of a larger network of tunnels that run below much of the middle of the country. We squat-walked through and emerged after a few minutes, sweating and all but gasping for fresh air. I can't imagine spending multiple days down there, as many people did in order to survive air attacks.

Coconut Prison in Phu Quoc

Our last war-related stop was Phu Quoc Prison, also called the "Coconut Prison" on Phu Quoc island. Like Hoa Lo, the prison was first built by the French colonists to jail those considered especially dangerous to the colonist government. Many of the high ranking leaders of Vietnam were detained here before it became a prison used by South Vietnam to detain captured Viet Cong fighters, many of whom were mercilessly tortured. (The various torture methods are depicted in detailed, life-size models. Some are quite difficult to look at, much less imagine.)

Interestingly, signs at the prison stated that it was run by the "American Puppet Government," referring to the South Vietnam army, which was supported by the U.S.

Mike managed a smile as he made his way through one of the tunnels in Cu Chi

Lessons Learned?

All of these places provided perspective and particulars about what was an extremely complicated and even sadder situation. (Is war ever not complicated or sad?)

Still, after all that education, our favorite way to learn was hearing from Vietnamese people firsthand. Some of the most memorable lessons came from people we met who talked about their feelings or the stories they heard about the war from their parents.

At first, the few we talked to, notably all people working in hospitality/tourism, told us that no one in Vietnam harbors any hateful feelings anymore; that now that it's over, they just want peace. Multiple people told us that the Vietnamese are only looking ahead, thinking about the future and providing for their families. And that they love anyone who visits their country and spends money.

Based on all the smiling faces and the overly-helpful nature of hotel staff, that was easy to believe. But a few weeks in, we got some more unfiltered opinions.

In My Son, where we were touring temple ruins, our guide told us that there are indeed some older people who still "hate Americans" because they blame them for the death of relatives. He went on to explain that his father spent four years in the Cu Chi Tunnels and all of his father's brothers died in the tunnels during one attack.

But it is true that many Vietnamese are happy to see so many visitors arriving. For the most part, they are very proud of their country and eager to show off how far they've come. When we were trekking in Sapa, we arrived at Lao Chai village and Lan, our guide, exclaimed, "I love my country!" She was beaming.

The past is the past. There's no going back to change it. But traveling somewhere with a history like Vietnam's without learning about it would be irresponsible. When it comes to travel, ignorance cannot be bliss. For to leave without understanding a place and, more importantly, its people, is to leave without truly having experienced it.

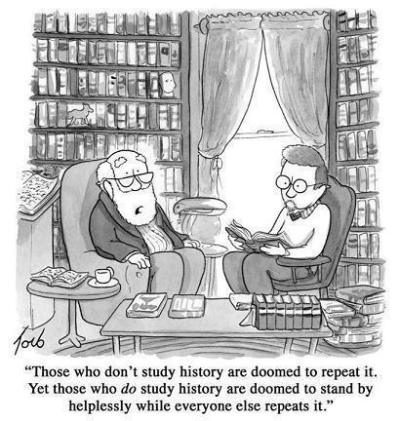

I'd like to say that people need to know what happened so that history does not repeat itself. But, as we reflected on our surprise, sadness and even shame at what we'd learned, we realized that similar situations are still happening in the world today.

And since I can't think of a nice little "bow on top" way to finish this post, here's this: